Milford House

Milford House’s origins trace back to the medieval domain of Sutton Coldfield, evolving from a manor site to a mid‑Victorian mansion.

By 1860, the site was in the hands of Lord Somerville, who had built a new house there to replace the old manor. After his death in 1864 and the passing of the estate to his sisters in 1870, the property continued as a substantial residence within Sutton Coldfield

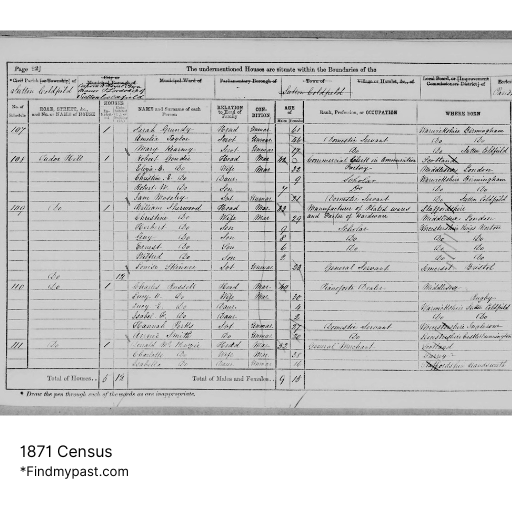

By the 1871 census, it was the home of a prosperous manufacturer and his family. This is where the stories begin.

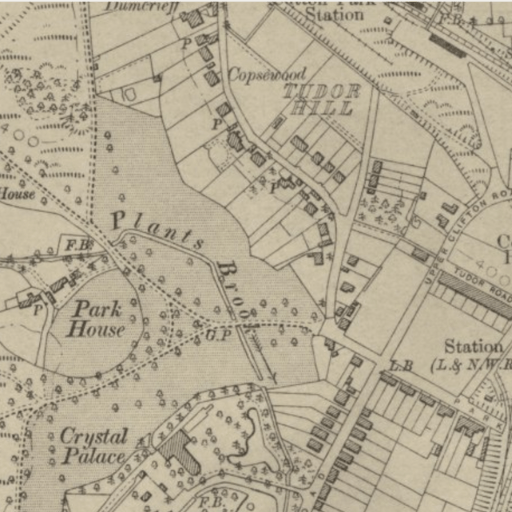

A map from around 1889 of the Sutton Coldfield area showing Tudor Hill.

William & Christine Sherwood

In the bustling industrial heart of Caldmore, Walsall, the year was 1841, and the Sherwood household was a hive of energy. Robert and Mary Sherwood, a hardworking couple in the throes of the early Victorian era, lived with their seven children, a true chorus of youthful energy.

Among them was William Sherwood, born into the middle of this vibrant family. Unusually for a working-class family of the time, they employed a 16-year-old servant named John, a sign that the Sherwoods were doing reasonably well.

Walsall, during the 1840s, was alive with industry, lock-making, leather goods, and metalwork thrived, and boys like William would have been surrounded by the clang of workshops and the scent of coal smoke. It was in this environment that he likely developed his interest in metalwork and manufacturing.

By 1860, William was a man of means and ambition. He married Christine, a woman born in 1842, likely from a family with similar social standing. The marriage took place in Kings Norton, a leafy suburb south of Birmingham.

By 1861, the newlyweds were living on Pershore Road in Edgbaston, an area growing in affluence. William had begun carving out a career as a printer of plated silverware, a trade requiring both precision and artistry. The Sherwoods had a servant named Martha, a clear sign of their emerging middle-class status.

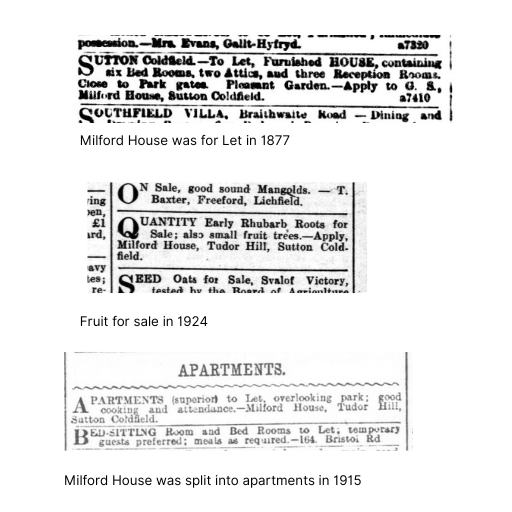

Ten years later, in 1871, the Sherwoods had flourished further. They lived at Milford House, Sutton Coldfield. William’s profession had evolved, he was now listed as a manufacturer of plated wares and factor of hardware, overseeing production and possibly running or owning his own workshop or firm.

They were raising four sons, Herbert (9), Guy (8), Ernest (6), Wilfred (2) and they employed a general servant named Louise to help with household duties.

By 1891, the family had moved again, living on the High Street, the town’s central thoroughfare. William was described as a manufacturer of electroplate, part of the thriving Birmingham metalware and electroplating trade that had spread to nearby towns. Electroplating had become a booming business by this time, with silver-plated goods adorning the homes of Britain’s expanding middle class.

In 1901, William retired. The Sherwoods had moved to Wentworth Road, Sutton Coldfield, a desirable address in a growing suburban town. Living with them were two of their sons, Nigel and Harold, both working as clerks. They employed Elizabeth Willet, a cook, reflecting their continued comfortable lifestyle.

William Sherwood passed away in 1920, closing the chapter on a life that had stretched from the smoke and sweat of early Victorian Walsall to the calm prosperity of leafy Sutton Coldfield. He was laid to rest in Sutton Coldfield Cemetery.

By 1921, Christine, remained in Sutton Coldfield. She lived in a quiet household with a visitor Jane Speek (80 and from Canada), a maid, and a nurse, surrounded, by the echoes of a full and dynamic life.

Christine died in 1927, closing the Sherwood legacy of the 19th century, a family that rose through ambition, metal, and modernity to leave their mark on Birmingham’s industrial tapestry.

Joseph & Sophia curtis

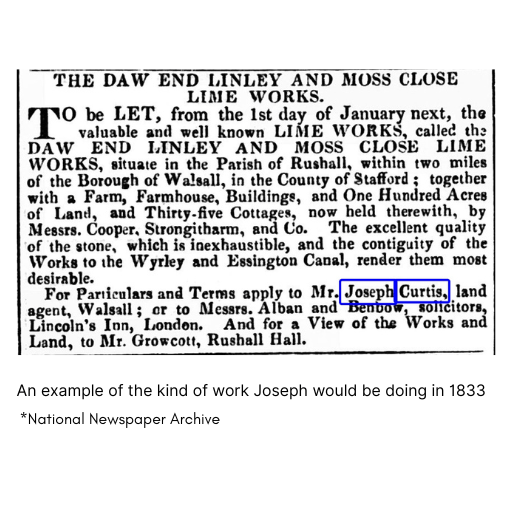

Joseph Hawthorn Curtis was born in 1819 in Walsall, Staffordshire, into a life that would weave through enterprise, estate management, and multiple chapters of love. His father, also named Joseph, worked as a land agent, a role that shaped the young Joseph’s future path.

By 1833, the ambitions of Joseph came into public view: he advertised farm property, 100 acres, cottages, and a farmhouse in The Globe newspaper, giving us a glimpse into the scale and type of estates he managed.

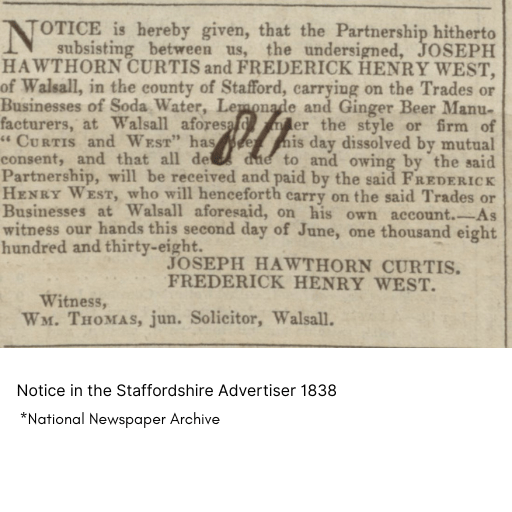

In 1838, he co-owned Curtis & West, a soda water, lemonade, and ginger beer factory in Walsall. He later sold his share to Frederick Henry West, marking his exit from beverage manufacturing, perhaps to focus on estate work.

By 1841, census records show him living with his father, a probable mother Hannah, his sisters Ellen (11) and Clara (3), and brothers Alfred (8) and Henry (infant).

In 1857, at the age of 38, Joseph married Sophia Perry in Castle Bromwich, a union that would mark a fresh start at a different home, far from Walsall’s brewery air.

By 1861, census records place Joseph at Perry Point, Aldridge Road, West Bromwich, working again as a land agent, with two servants, but without Sophia present, suggesting she may have been visiting or travelling.

By 1871, the couple resided at The Woodlands, Handsworth, with their nephew Alfred, and visitor Elizabeth Wilmot, while employing two servants. Their household appeared solid and well-managed.

By 1881, Joseph and Sophia were living in Milford House, alongside Sophia’s sister, Clara Whattoff, and servant Susan. Despite no occupation listed for Joseph, the home reflected genteel stability until Sophia’s death on 23 September 1887.

In 1889, Joseph found companionship again—in marriage to Mary Wilmot, sister of Elizabeth Wilmot (who stayed with the family in 1871). He continued to live at Tudor Hill until his own death on 26 February 1897.

In the Walsal Advertiser on the 6th March 1897, it was said that his ‘name would be familiar to many’ at the Queen Mary’s Club showing he was an active and treasured member of the community.